What Is Complete Civil Disobedience?

An unexpected yet readily identifiable common theme binds Egyptian activists together in their call for Mohammed Morsi and his government to step down in 2013, Sudanese protesters in the aftermath of the 2019 Khartoum massacre and the 2021 coup d’état, members of the ‘yellow vest’ movement in France, and supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. Despite evincing utter disparate political stances, all four movements appear to rally under an ostensibly new watchword: “complete civil disobedience.” Yet, complete civil disobedience has an extensive history. It is an idea that Mohandas Gandhi developed early on to conceptualize nonviolent resistance. In his words, “Complete civil disobedience is a state of peaceful rebellion—a refusal to obey every single State-made law. It is certainly more dangerous than an armed rebellion.” In this paper, I situate the idea of complete civil disobedience in Gandhi’s legal and political thought as well as contextualize it in the history of anticolonial anarchism. I also explore the moral, legal, and political challenges that arise from this form of disobedience.

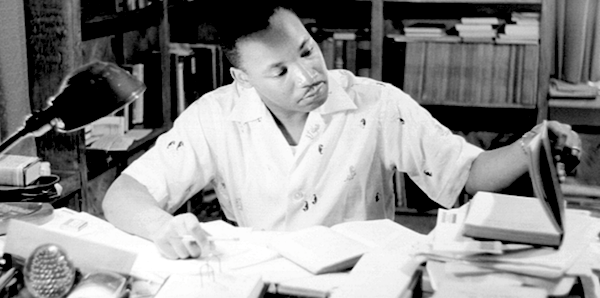

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Genealogies of Civil Disobedience

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham City Jail” (1963) is usually considered, along with his well-known speech “I Have a Dream,” one of the most important documents of the civil rights movement. Between 1967 and 1999, the “Letter” was reprinted at least 50 times. Since the 1990s, this figure has surely increased. Until this date, however, little attention has been paid to the variations between its different versions. By starting from a variorum edition of the letter, I analyze in this paper the different genealogies of civil disobedience formulated by King during the 1950s and 1960s and show how they can help us shed light on the development of his conceptions of (non)violence and legitimate resistance during this period.

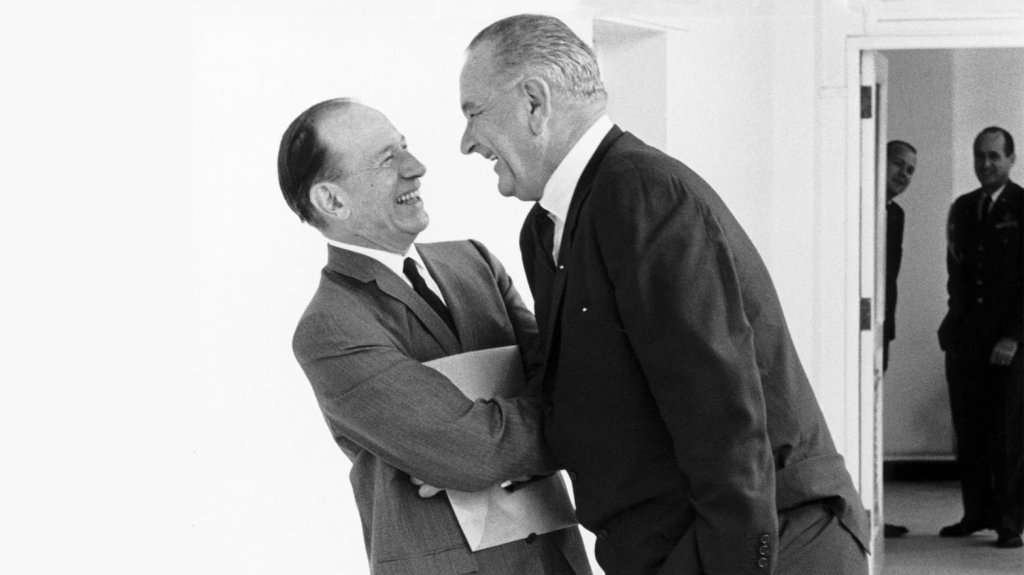

Toward a Global History of Abe Fortas’s Concerning Dissent and Civil Disobedience

This paper traces the global history of United States Supreme Court Justice Abraham “Abe” Fortas’s 1968 book, Concerning Dissent and Civil Disobedience. Published in the midst of a corruption scandal that would eventually force Fortas to resign from the Supreme Court, the book criticized the use of civil disobedience by activists opposing the Vietnam War. I show that Fortas’s book contributed to reconfiguring the debate on the justification of civil disobedience in the United States, both inside and outside academia. Drawing on largely overlooked archival materials, I also reveal that this debate had repercussions throughout the world and played a key role in American foreign policy during the Cold War era. With support from the U.S. government, the book was translated and published in Brazil, France, and Japan—and shaped debates about civil disobedience in the context of international struggles against student radicalism. Reframing the history of civil disobedience around this little known legal figure has, I argue, broad implications for the work of historians, philosophers, political scientists as well as activists and political commentators, who follow unknowingly in Fortas’s footsteps when they argue whether civil disobedience should be public (and never clandestine), nonviolent (and never coercive), and reformist (and never revolutionary)—features of civil disobedience that became commonplace in the course of worldwide debates about Fortas’s book. Fortas—and not Henry David Thoreau, Mohandas Gandhi, or Martin Luther King, Jr.—remains until today the most influential theorist of civil disobedience. In retracing this history, I aim to theorize how idea(l)s of law and order, predominant in the American discourse on civil disobedience in the late 1960s and early 1970s, entered the international sphere amid fears that radical movements of resistance inspired by anticolonial struggles, antiwar protest, and the African American civil rights movement could destabilize the liberal international order. I also probe the fundamental role of books as well as publishing and translation projects in the development of American soft power during the Cold War.

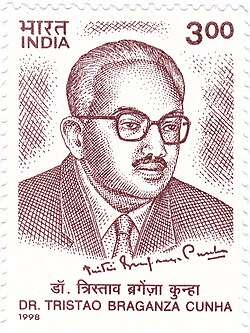

What Is Decolonial Annexation?

Should Goa, Daman, and Diu (collectively known as Goa), territories in the Indian subcontinent under Portuguese colonial rule since 1510, be annexed as a federal state of postcolonial India, remain an overseas province of Portugal, or become an independent nation-state? In the decade following India’s independence from the British Empire, this question progressively occupied an ever-greater place in early Cold War debates and conflicts. In the late 1950s, Tristão de Bragança Cunha, “the Father of Goan Nationalism,” influentially argued that Goa had rightfully belonged to India since precolonial times and that its decolonization should take the form of a peaceful “re-union” with it. In this paper, I reconstruct Cunha’s theories of (non)violence and imperialism to shed light on his critique of what he called the West’s “policy of cold war,” his advocacy for the peaceful reunification of Goa and India, and his efforts to justify the People’s Republic of China’s control, if necessary by force, over Formosa (today’s Taiwan), Hong Kong, and Macau. I subsequently discuss why the problem of how to assess the political legitimacy of decolonization via annexation or reunion remains, despite its seemingly settled nature, one of the most significant legacies of the Cold War in the exercise of popular sovereignty in the Global South. This problem, I argue, ultimately leads us to recast the history of colonization and reconsider what decolonization through annexation – and without popular participation – entails. From 1918 onward, Woodrow Wilson’s and Vladimir Lenin’s calls for national self-determination, respect for the consent of the governed, and nonannexation contributed to reshaping anticolonial political thought. But for an often-neglected tradition of anticolonial thinkers such as Cunha, annexation (and reunion, as its peaceful alternative) was counterintuitively seen across the twentieth century as a decolonial or decolonizing praxis.

Ungrateful Disobedients: Liberal Pluralism, Indigenous Resistance, and the Colonial Politics of Recognition

Michael Walzer’s philosophy of civil disobedience proves an enlightening entry point into how political liberalism addresses the question of recognition. In his 1967 article for Ethics, “The Obligation to Disobey,” Walzer draws on the work of British pluralists John Neville Figgis and George Douglas Howard Cole, as well as French sociologist Émile Durkheim, to theorize disobedience as a social fact derived from our associative obligations. Many individuals experience lawbreaking as a moral obligation, Walzer’s argument runs, because they belong to a plurality of social associations or groups whose norms can conflict with what the state requires. At first sight, this pluralist theory of disobedience sheds productive light on what is social about social movements, by emphasizing how community building, intragroup recognition, social belonging, and solidarity networks are fundamental to understanding political resistance. Walzer’s liberal communitarianism contradicts its own pluralist premises, however, by (re)centering the liberal state and suggesting it can demand allegiance from its members when it provides them with “genuine goods” or “services” such as security. By tacitly accepting and enjoying such goods, individuals and associations find themselves caught in a trap: they need to recognize the state’s authority, because it can be said to recognize their most basic needs. In this essay, I theorize this trap, which can be identified in various political philosophies and the commonsense conception of political obligation, as an overlooked form of what Glen Coulthard conceptualizes as a “colonial politics of recognition.” By drawing on the work of Indigenous activists and scholars, I shed normative light on how this trap concretely serves to delegitimize both civil disobedience and more radical resistance to the state as forms of betrayal and ungratefulness, even in the face of grave injustices.